A Conference Board of Canada report that paints a picture of Canada as a land of copyright pirates is itself tainted by plagiarism, according to one of Canada’s top experts on Internet law.

In a press release and trio of reports, the Conference Board brands Canada “the file-swapping capital of the world.”

In its Intellectual Property Rights in the Digital Economy report, the non-profit organization lays out the case for Canada’s inadequate copyright protections and recommends several actions to help the country get up to snuff.

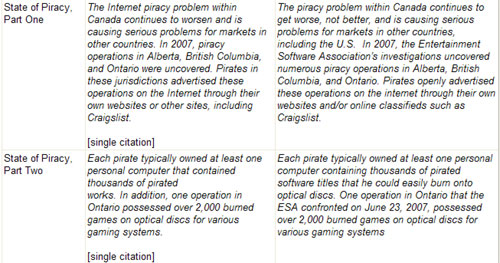

But that report itself plagiarizes texts from the U.S. movie, music and software lobby group International Intellectual Property Alliance (IIPA), says Michael Geist, Canada’s Research Chair in Internet and E-Commerce Law at the University of Ottawa.

Geist made the allegations in his blog on Monday morning.

“It’s not a charge that anyone would level carelessly. I’m a law professor,” Geist told ITBusiness.ca in a phone interview. “The lack of attribution and even the very mild paraphrasing, without attribution, would be treated as plagiarism in most institutions.”

The IIPA report is dubbed “2008 Special 301 Report: Canada.” It recommends that Canada be placed on the U.S. “Priority Watch List” for its lack of progress in updating its copyright law to meet with international treaties.

And the IIPA got it’s wish.

Canada was recently been placed on the U.S. Priority Watch List for allegedly failing to protect intellectual property.

Washington’s annual report on intellectual property offenders was released by Stanford McCoy, assistant U.S. trade representative for intellectual property and innovation. The report expressed “serious concerns with Canada’s failure to accede to and implement the WIPO (World Intellectual Property Organization) Internet treaties which Canada signed in 1997”

The World Intellectual Property Organization is the United Nations agency that sets the standard for international copyright laws.

It said Canada’s “weak border measures” continue to be a serious concern for intellectual property owners.

Canada’s elevation to the “priority watch list for the first time”, WIPO said, spoke to “continuing need for copyright reform as well as continuing concern about weak border enforcement.”

Canada’s placement on the priority list had been welcomed by the International Intellectual Property Alliance — a group that includes high profile organizations including Microsoft, Apple, and Paramount Pictures.

Geist highlights several examples of very similar paragraphs between the two reports.

Meanwhile, despite Geist’s allegations of plagiarism, the Conference Board is standing behind its report.

“While Mr. Geist charged the Board with lack of attribution in several instances, in fact, only one citation is missing,” a statement on the group’s Web site says. “We have corrected the missing citation in the report and we apologize for the oversight … We also acknowledge that some of the cited paragraphs closely approximate the wording of a source document.

But Geist also calls into question some of the key facts cited by the report to support the case that Canadians are practicing rampant digital piracy.

Canadians make 1.3 billion illicit downloads compared to just 20 million legal downloads, the report claims. But the source of that information is a 2006 Pollara survey of 1,200 respondents cited by the Canadian Recording Industry Association in a January 2008 press release.

“There’s no other way to put it — it’s factually inaccurate and its deceptive,” Geist says. “You can’t ask such a small sample size relative to the rest of the Canadian population, and then make these claims. It’s also a self-reporting mechanism that doesn’t really tell you whether it’s unauthorized or authorized.”

The report also cites an Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) report as evidence that Canada has the highest per capita incidence of unauthorized file swapping in the world. But the actual report only labels Canada as the highest per capita rate of peer-to-peer (P2P) protocol, and does not determine whether it is authorized or unauthorized.

The data is also five years old and based on activity of 30 OECD countries, not the entire world.

“To claim we’re the leading unauthorized file swapping capital of the world based on an old OECD study, that’s incredible,” Geist says. “On top of that, tax dollars went towards paying for [that report].”

Ontario’s Ministry of Research and Innovation helped fund the Conference Board’s report, alongside copyright lobby groups such as the Canadian Anti-Counterfeiting Network, Copyright Collective of Canada, and both the U.S. and Canadian Chambers of Commerce.

While the ministry didn’t commission the report, it did provide $15,000 to the Conference Board for its upcoming conference Intellectual Property Rights: Innovation and Commercialization in Turbulent Times. Some of that money was used towards the report, says Grahame Rivers, press secretary for John Wilkinson, Ontario’s Minister of Research and Innovation.

“These are serious allegations. We take any charge of plagiarism seriously,” Rivers says. “We will be following up and look forward to hear what they [Conference Board of Canada] have to say about this.”

The exchange between Geist and the Conference Board is not the first time the debate over Canada’s copyright laws has been controversial. The minority Conservative government had Bill C-61 on the table to enact copyright reform, but it was killed when an election was called Sept. 7, 2008.

Bill C-61 was been called Canada’s version of the U.S.Digital Millennium Copyright Act by critics who complained it was too strict in preventing legitimate copying of digital media. It would also put the onus on copyright holders to enforce their rights by suing those who infringed upon them.

Canada remains in need of copyright reforms to meet obligations of WIPO treaties, says Brian Isaac, chair of the Canadian Anti-Counterfeiting Network.

“Canadians tend to be more likely to infringe copyright than in many other industrialized nations,” he says. “We’re risking becoming a haven for some of the people who are trying to profit off of Internet piracy.”

A tougher mandate for the Canadian Border Services Agency to enforce copyright law is one thing the network would like to see. It is also recommended in the Conference Board’s report.

“The key is ex-officio power and the ability to communicate information that will be effective in dealing with this stuff,” Isaac says. “They need to be able to detain goods.”

To comply with WIPO Internet treaties, Canada must prohibit the deliberate alternation of digital rights management information. It must ensure that copyright holders are able to use technology to protect their licences and works online, and those who find ways around that protection are punished.

Canada should do this by outlawing devices or software designed to circumvent such protective measures, the Conference Board says.

The Board bills itself as an objective research group without an agenda. Its slogan is “insights you can count on.”

“The Conference Board of Canada has compounded its mistake by standing by its report,” Geist says. “In doing so, it has done little more than further undermine its credibility.”

No spokesperson from the Conference Board was able to respond to an interview request before deadline.

With files from Joaquim P. Menezes