Imagine walking into a meeting and encountering not just your current co-workers, but all your colleagues and managers from jobs past, along with your spouse, your college drinking buddies, your Senior Prom date, and, off in a corner, your adolescent son, busy telling your boss how many hours he logs in every day playing Grand Theft Auto.

It’s not a nightmare, it’s Facebook.

If you’re anything like the 200 million users on the burgeoning social network, you probably didn’t give enough thought when you first signed on to which friend requests you accepted, or whom you invited via the Friend Finder. Now you’ve got a dangerously random group of friends and friends-of-friends sharing — and over-sharing — information, sometimes without your even being aware of it.

The “he told two friends, and they told two friends” syndrome can be embarrassing in your personal life, but potentially much more serious in the world of work.

Even if you’re careful in posting work-related news in your status updates and comments on others’ walls and feeds, are each and every one of your friends as cautious as you are?

One buddy writing “Yo, how did the layoffs go down?” on your wall is enough to cause havoc in your office – particularly if layoff day hasn’t yet happened.

Even more troubling: the online behavior of your direct reports, who, demographically speaking, are likely to be both more enthusiastic and less discriminate in their use of Facebook and other social networks.

“Younger people are using Facebook on a quasi-professional basis to build stronger relationships with people,” says Michael Argast, director of Global Sales Engineering at security vendor Sophos Plc. “That means they’re sharing a lot of information with a lot of people on a regular basis.”

Again, if the information they’re sharing is what five albums have most influenced their lives, fine. If the information they’re sharing is that your division might miss its new product ship date “by a mile!!!!!!,” that’s not fine.

Even more alarming, a new tool from Facebook lets users see their friends’ activity streams from cell phones or computers without having to be logged into their Facebook home pages, which could potentially spread unwary users’ updates and comments even faster than before.

In short, the more ubiquitous Facebook becomes, the greater its potential to muck up office life — and make your job as a manager just that much more treacherous.

And these are just the accidents. The sea of information on Facebook is also starting to attract information pirates, identify thieves and malware distributors.

The best defense against these threats is awareness of the kinds of problems that can arise and how to head them off, coupled with a true understanding of the medium. Facebook does indeed offer tools (see Facebook’s privacy options) to help its users better control the flow of information, but it’s up to your employees — perhaps with a little coaching from you — to learn how to use them and then put them into play.

Until that happy day, here are some of the top inter-office challenges posed by Facebook:

Too many “friends”

All but the most cautious Facebook users wrestle with the problem of having too many disparate groups of people as “friends” — co-workers, family members, drinking buddies, church colleagues and so forth. “Facebook has been relatively good about providing ways for users to separate friends into groups,” says Argast, “but the tools are not that easy to find.”

Separate from the social challenge is the issue of people, particularly younger Facebook users, becoming friends with people they don’t know well, or even at all. “Facebook doesn’t have our normal social mechanisms for validating someone,” Argast points out — and many users, especially people who use Facebook to network, are reluctant to turn down a friend request.

(This is less of a problem for older users who have “different social inhibition mechanisms,” as Argast puts it — in other words, they’re not as comfortable with revealing personal information to online acquaintances.)

Even the cautious among us are likely to be friends with former colleagues who now work for competitors, and those innocuous relationships can potentially cause problems.

Imagine you’ve just had an innocent lunch with a former co-worker and discussed joining her fantasy baseball league.

You come back to find a post on your wall that reads, “Great talking to you, and I’ll be sure to let you know if there are any openings.”

What kind of rumors will that start among your staff and colleagues?

Information travels too far

The currency of Facebook is the information that friends choose to share with one another — status updates, wall posts, external Web links, photos, videos, survey results, application feeds, and comments on all of the above.

The unending flow of data from friends and supposed friends can easily get out of hand — who among us hasn’t 86ed a friend who cluttered our feeds with inane chatter about whether their baby was napping or awake?

But the real problem isn’t the nature of the information but the fact that the structure of Facebook makes it easy for information to spread beyond the people it was intended for.

Say a Facebook user posts a funny picture of a cat. If one of her friends — your employee, as it turns out — comments “LOL,” there’s no harm done.

But what if your employee instead writes, “thanks. i rilly needed a laugh this morning — everyone here is freaking cuz our servers are down.” Suddenly lots of people she may not know, and you certainly don’t, are now aware of your company’s technical difficulties, all in lightning-quick Internet time.

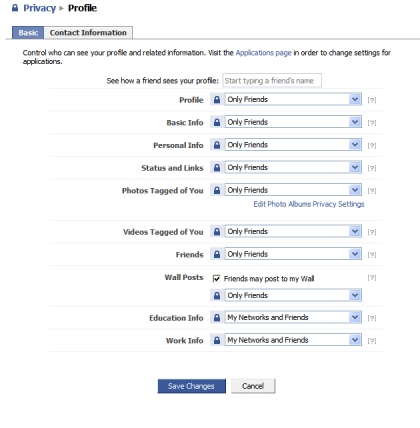

A simple change of settings can solve many vulnerabilities — that is, choosing to show profile, basic info, personal info, photos and so forth only to “Friends” rather than Facebook’s other options (“Friends of Friends,” “My Networks and Friends,” or the truly indiscriminate “Everyone.”)

Choose “Only Friends” to keep your Facebook profile information as private as possible.

But the real problem with Facebook (and all social media), says Filiberto Selvas, a social media consultant and author of the Social CRM blog , is that people jump into using them without really understanding how they work.

If you or your employees haven’t taken the time to explore the social network site’s privacy controls, then “you don’t have any idea of who is connected to whom on the other side,” warns Selvas. “Once you put in the content, it may not be under your control any more.”

The consequences of letting the wrong people see embarrassing photos or inappropriate postings have gotten a lot of attention in the media, but users’ awareness may be lagging behind.

A March 2007 survey by the Ponemon Institute , a privacy and data-protection think tank, found that 23 percent of hiring managers checked social networking sites for data about job candidates. It’s a trend that’s not going away anytime soon, says Mike Spinney, an analyst with Ponemon. “The growing popularity of Google, awareness and rapid adoption of social networking utilities, and ongoing media attention strongly suggest that the practice is more widespread today than it was two years ago,” he reports.

Nevertheless, a summer 2007 study by the workforce consulting firm Adecco found that “66 percent of Generation Y respondents were not aware that these seemingly private photos, comments and statements [on social networking sites] were audited by potential employers.”

Facebook encourages people to join Networks — affiliations of users around shared interests and categories, either set up by the site itself (region, workplace, high school, or college) or created by other users. But Facebook’s default setting is to make the profiles of network members visible to everyone in the same network. That means, unless they change their settings manually, your employees’ wall posts, personal info, and photos can easily be viewed by others, whether they’re direct friends or not.

Kim Goldberg, an insurance claims manager, discovered that connection the hard way. She relates: “I went on a job interview at a company I had worked for in the past. I was walking around the office visiting old friends, and one said, ‘I heard you just made plane reservations to go to Florida.’ I was shocked — how could she know that? I hadn’t talked to her in years, and the trip was still a surprise to my own kids!” Even more urgent, Goldberg certainly didn’t want her prospective new employer to know she’d need time off so soon after coming on-board.

“I asked how she knew,” Goldberg continues, “and she said she saw it on my husband’s Facebook page. I was so confused. She and my husband were not even Facebook friends.”

Goldberg eventually figured out that the former co-worker and her husband were both part of the same regional network on Facebook, and that was how she obtained access to his personal page. “My husband immediately changed his privacy settings,” Goldberg concludes, “but the incident could have cost me the job.”

In the era of corporate layoffs, stories abound of ex-employees using Facebook and Twitter as an instant support mechanism during and immediately after their downsizing.

But when news of layoffs happens in real-time — spreading quickly to a wide group of interrelated people, sometimes before other employees have been formally notified of their fate — the burden lands on corporate communications to stay ahead of the story, as executives from American Express and Serena Software discussed at an employee management conference late last year (see video ).

Facebook blurs the line between worker and boss

Facebook can be a swamp for boss and employee alike as everything from romantic entanglements and political views to over-sharing about recreational substance use makes its way from the digital world to the physical office.

If your top programmer announces on Facebook that she’s pregnant, but neglects to tell you in real life, is this information you now “know” for planning purposes or not? If a long-time contract programmer shares in his status update that he just got a contract to write a book, are you out of line in asking if he still has time for your projects?

Beyond discretion, there are potential legal issues as well. If one of your direct reports posts links on Facebook to “adult” YouTube videos, could another employee maintain that it creates a hostile workplace environment? Is it your responsibility to do something about it? As with workplace harassment issues from 20 years ago, the answer seems to be “nobody knows — or at least not yet.”

Given that uncertainty, managers are best off not “friending” current work colleagues, and definitely not subordinates, says Lynette Fallon, Executive VP HR/Legal at Axcelis Technologies, Inc. “You should tell your co-workers that it’s nothing personal, it’s just your policy not to mix friends on Facebook,” she advises.

Beyond that, managers with active Facebook subordinates should at the very least encourage them to keep co-workers and outside friends on two different Friend Lists.

Facebook’s apps and photos can leave you vulnerable

Even if you and your employees are careful not to share sensitive information in wall posts and status updates, it’s still easy to inadvertently spill the beans. The Internet is chock-a-block with applications that bring data into Facebook from outside sources — again, often without the user’s realization.

As just one example, “There’s a way to capture Delicious bookmarks to Facebook so that everything you bookmark gets posted to your feed,” says Selvas.

If your research team is using Delicious to bookmark source pages and haven’t checked their privacy settings, their work may be getting propagated on Facebook, giving friends and potentially competitors alike a pretty good idea of what your company’s next big idea is going to be.

That goes for individuals too — if you bookmarked several articles about becoming an IT consultant , that information should be for your eyes only, not all your work colleagues on Facebook.

Other applications display the books you’re reading, the movies you just bought tickets to, and the stations you just set up on Pandora .

All this information is time-stamped when it’s displayed. Even if you don’t mind your boss knowing you bought tickets to I Love You, Man, do you really want her knowing you bought them while you were on the clock? If you’re working on a non-company project on company time, same problem. Unless you — or your co-workers — know to turn on the controls , all your Facebook friends can see what you were really doing during that endless conference call.

Another concern, Selvas says, is the Facebook tool for tagging people who appear in posted photographs: what if someone tags your photo among the attendees at a conference, he asks, where your presence implies something about ventures your company might be considering or jobs you might personally be angling for? You can remove the tag yourself, but only after he fact. While you can protect yourself beforehand by using Facebook’s privacy settings to restrict who gets to see photos you’re tagged in, even an untagged photo of you can still cause problems if your face is recognizable.

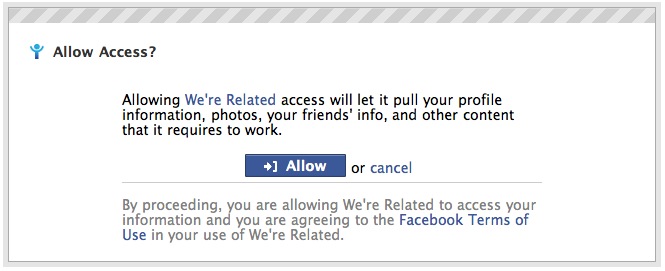

Be wary of Facebook applications, which can gain access to your profile information, photos, friends’ information and other data.

A further issue is the fact Facebook applications gain access to — as the warning screen tells you — “your profile information, photos, your friends’ info, and other content that it requires to work,” whether they need it or not.

In 2007, Adrienne Porter Felt, then a computer science student at the University of Virginia and now a student at U.C. Berkeley, and David Evans, an Associate Professor of Computer Science at the University of Virginia, did a survey of the top 150 Facebook applications and found that “90.7% of applications are being given more privileges than they need” to perform their intended functions.

The researchers haven’t updated those earlier findings, but Evans says he suspects the results would be pretty similar. “If anything, the applications are getting more complex,” he says. “And there is also an emerging model for third-party advertising networks embedded in applications, which has further privacy risks.”

Facebook’s policy does require application developers to delete user information after 24 hours, and, according to a Facebook spokesperson, the company has an enforcement staff to monitor compliance. Nevertheless, such wholesale acquisition of information illustrates the problem of retaining any kind of control over content you or your employees post.

And then there’s the issue of how Facebook itself retains information posted by its users. The company stirred up a firestorm earlier this year when it made a change to its Terms of Service that gave the site ownership of all posted information, even after users had deleted their accounts. The immediate negative reaction forced Facebook to retract the policy and craft a new Terms of Service agreement, but again, it illustrates how volatile the data-ownership issue continues to be.

Security threats still apply

Part of the appeal of Facebook is that it offers an alternative to regular e-mail and its spam, scam, and phishing issues. If you get a message on Facebook, theoretically it’s from someone you know, or at least a friend of someone you know. But that’s changing, as scammers and malware distributors figure out how to adapt Facebook for their own ends.

One growing problem is with people pretending to be someone they’re not. In January, for example, Silicon Alley Insider documented the efforts of a Nigerian scammer to convince a Facebook user to send money to him by posing as one of the victim’s friends, whose Facebook account the scammer had managed to gain access to.

Similar approaches can be made without having to actually take over someone’s account. A scammer could join a network or a group, for example, and start sending messages to everyone in the group. Since users are less suspicious of messages they receive on Facebook than they might be of an e-mail — especially if the person on Facebook is part of their network — they may be less guarded with their information.

Research by Sophos discovered that 41 percent of Facebook users “will divulge personal information — such as e-mail address, date of birth and phone number — to a complete stranger.”

Even if such slips don’t directly reveal information about a company, they can be useful in constructing a social engineering attack. The more bits and pieces of personal data about you and your staff a malefactor can acquire, the easier it would be for him to worm valuable company information out of them as well.

There have even been instances of Facebook being used as a way of distributing malware, says Argast. E-mails sent to Facebook groups or networks from apparent acquaintances have contained links to malware sites.

And last August, Sophos posted a warning about a message being left on Facebook users’ walls urging them to watch a particular video. Clicking on the link took users to an outside Web page that urged them to download an executable to watch the movie. The executable turned out to be the Troj/Dloadr-BPL Trojan horse.

Should you ban Facebook from the office?

But the solution, Selvas says, isn’t for employers to simply forbid employees from participating in social media; rather, they should educate workers not only as to what the dangers are, but on how to use the tools available on Facebook to control the propagation of information as much as possible.

He compares the situation with Facebook to the early days of e-mail. Remember when people would hit Reply All and then make a sarcastic comment about the boss’s message? It took a while for people to develop proper e-mail etiquette, and similarly it will take a while for people to learn to navigate the perils on Facebook, Selvas says. Education can go along way toward making that happen. (See Social networks meet corporate policy, below, for some companies’ internal guidelines.)

Bottom line? Facebook doesn’t call for new principles, Selvas says, just smart application of the old ones. And the constant reminder that you and your employees are in public when you’re on Facebook. As Selvas sums up, “Don’t do anything on Facebook you wouldn’t do in an airport.”

San Francisco-based Jake Widman is a frequent contributor to Computerworld.

Source: Computerworld.com