If you think your business is “too small to fall” victim to hacker techniques such as those used against Google in January 2010, the PlayStation network breach or the recent cyber attack on several Canadian government agencies, think again.

Hacker techniques used in massive state-sponsored attacks are moving downstream and are now being used on small and medium sized businesses (SMBs) according to Internet and e-mail security firm Websense Inc.

“We are now looking at phase two of the malware adoption lifecycle,” according to Patrik Runald, a senior threat researcher for the security company. “Targeted attacks are hitting every single business that uses the Web and e-mail. SMBs are no longer exempt.”

What Runald calls the “phase two” chiefly involves the recycling of high-profile attack techniques used in so-called advanced persistent threats (APTs) into cheaper exploit kits that low-level hackers are now able to purchase online on use against smaller targets.

“APT is originally from the Air Force,” says Ryan Kalember, director of product marketing for HP ArcSight, during our discussion of Ponemon Institute’s annual study on cybercrime. The term arose as Air Force shorthand to describe endless, unremitting network attacks coming from mainland China – the People’s Republic of China (PRC). “It’s a running joke in the industry that APT is short for PRC,” he adds.

But the phrase APT has evolved into something broader. It suggests the effort not just by nation-states, but also industrial competitors, along with any hired-hand assistance, to infiltrate the networks of targets to steal important and sensitive information, such as intellectual property.

Whereas malware used in high-profile attacks typically cost what Websense calls “innovator hackers” hundreds of thousands of dollars to develop, these exploit kits can be bought by “late adopter hackers” for as low as $25 and some even turn up free on the Internet, said Runald.

While attacks on high-profile organizations tend to target sensitive corporate or government information for industrial espionage purposes, Runald said, exploit kits are generally used to steal user’s personal or credit card data.

“If your business deals with client information on the Web of carries out online transactions, you could be targeted,” he said.

Malware adoption lifecycle

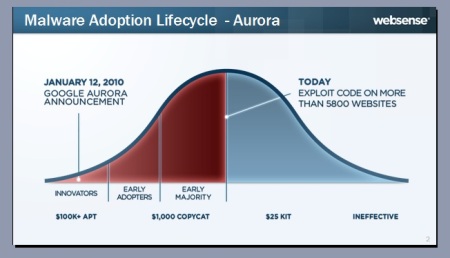

In the case of the Aurora attack on Google, the search engine announced the incident on January 12 last year. The hackers managed to get deep into Google’s network and gain control of the company’s internal systems.

Three days later, the attack code was already publicly available. Within weeks, the exploit was in the wild. Eighteen months after the attack on Google, there were some 5,800 exploits using the same code, according to Websense.

“Even when target companies manage to develop a patch, once that patch is release hackers reverse engineer it and come up with a new exploit. In other instances variants or copycat malware are developed,” Runald said.

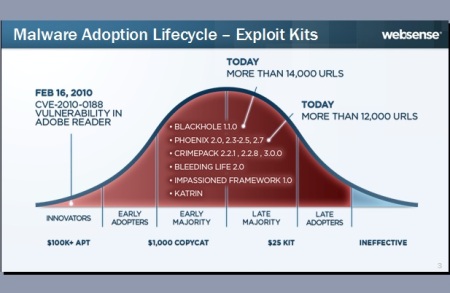

The new exploit is sold to lower level hackers, he said. Something like this happened with the APT used on the Adobe Reader vulnerability in February last year, according to Websense.

The malware used for that exploit spawned a market for $1,000-copycat malware used more than 14,000 infected URLs. The copycat malware further trickled down to a $25-exploit kit market which infects more than 12,000 URLs today, said Runald.

Hard to trace

Unfortunately, it is difficult to trace these attacks, according to Fiaaz Walji, Websense country manager for Canada.

“Businesses being attacked won’t see anything because it is all happening in the background,” he said. “Only 20 per cent of the sites under attack will give out an error message which could be a sign that it has being breached.”

He also said that security strategies that rely heavily on firewalls and anti-virus protection are not very effective against these attacks.

“Firewalls and AVs are reactive measures. They are typically signature-based protection that flag previously known threats,” he said.

The Security for Business Innovation Council, a group of 16 security leaders in corporations that include eBay, Coca-Cola Company, SAP, FedEx Corp., Johnson & Johnson and Northrop Grumman, last week said the APT problem is a top concern and it’s changing how you should look at security.

In their report, entitled “When Advanced Persistent Threats go Mainstream,” they said “Focusing on fortifying the perimeter is a losing battle” and “today’s organizations are inherently porous. Change the perspective to protecting data throughout the life cycle across the enterprise and the entire supply chain.”

The report added: “The definition of successful defense has to change from ‘keeping attacks out’ to ‘sometimes attackers are going to get in; detect them as early as possible and minimize the damage’ Assume that your organization might already be compromised and go from there.”

The focus, the report said, needs to be more on working with business managers to ascertain the “crown jewels” of the organization and protect these “core assets.”

(With files from Ellen Messmer, Networkworld US)

Nestor Arellano is a Senior Writer at ITBusiness.ca. Follow him on

Nestor Arellano is a Senior Writer at ITBusiness.ca. Follow him on